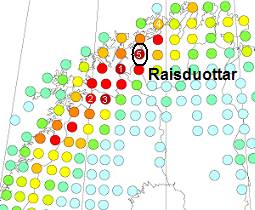

Raisduottar

belongs to the hotspot area of Fennoscandian

arctic-alpine biodiversity, streching from Duortnosjávri (Totneträsk) in

Swedish Lapland to Áltafávli (Indre

Altafjord) in

Numbers of lime-dependent arctic-alpine species

in different Atlas Florae Europae grids; according to

the situation in 2003, when the mapping was done for 20% of vascular plants.

(Even if lime-rich areas only cover 1-2% of the mountain/tundra landscape, they

stand for most of the biodiversity in Fennoscandia); Raisduottar is one of the

three hottest spots, along with the Gilbesjávri

(Kilpisjärvi, 1) and Duortnosjávri (Torneträsk, 3) areas

Geology and

climate contribute. Dolomite (red in the below scheme) is

most prevalent in the bottom of the Scandinavian mountain formation, and is

thus exposed along the eastern edge of the mountain chain and around “windows”

(granite outcrops). The arid climate along the edge counteracts leaching and

helps to keep pH in the neutral range. Moreover, reindeer aggregate to lime rich areas (grassy) – impact??

We conducted a preliminary study, utilizing gradients

in reindeer densities caused by differences in grazing policies between

Finland, Sweden and Norway and by the exclusion of reindeer from the dolomite

rich Malla in NW Finnish Lapland. All work was done

in areas where the dolomite cliffs get exposed (either along the east edge of

the mountain chain or around “granite windows” within the mountain chain). Main

result: local species diversity indifferent to grazing but the abundance of

arctic-alpine rarities correlates positively with grazing intensity (Olofsson

& Oksanen 2005). Correlations, however, have always alternative

explanations – finding correlations is just the start

for experiments.

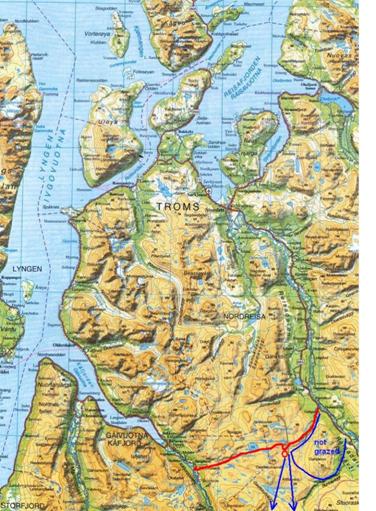

In Norway, migration is mandatory; to help to

keep the reindeer within legal summer ranges, the Sámi of Norway have built

hundreds of kilometres of reindeer fence

across the mountain– tundra landscape in the north. One of these fences – the

red line in the figure below - goes

right across the hottest part of the Raisduottar

hot spot, creating a sharp contrast of grazing intensity – strong grazing

pressure in the summer range, and practically non-grazed “dead angles” (the

area surrounded by a blue line). The reason: when reindeer are allowed to enter

the autumn range after marking in the corral (the red circle) they rapidly move

southwards towards the mushroom rich inland heaths within the angle limited by

the blue arrows; hence especially the area to the east of the corral has been

very little grazed since the 1960’s. (In spring the reindeer cross the area on

broad front as the fence is then snow covered but only graze on the most

exposed ridges, the rest is inaccessible)

Þ long

term experiment already done. On the west side of the corral the situation is

more complicated as a part of the area is now used as a calming down ground after

marking to ensure that the does do not move southwards so fast that their

calves would risk being left behind.

The impact of

the contrasting treatments is especially striking in relatively nutrient-poor habitats, where the

grazed (left, front) is dominated by unpalatable dwarf shrubs, while palatable grasses and forbs prevail on the intensely

grazed summer range (right, back), where productivity is higher, soils are warmer, and nutrient circulation is

rapid. (Olofsson

et al. 2001, 2004,

Olofsson

& Oksanen, L. 2002; see also Zimov et al. 1995,

Am. Nat. 146:765-794). It may indeed seem strange that unpalatable

plants prevail in a lightly grazed area, while palatable plants prevail in the

area with intense grazing pressure. However, light grazing is more selective

than heavy grazing, making defensive investments more profitable for plants.

Moreover, nutrient availability is dramatically higher on the intensely grazed

side, which increases the marginal costs of chemical defense, thus favoring

resilient plants (see

Oksanen, L. 1990. Predation, herbivory and plant strategies along gradients of

primary productivity. - pp. 445-473 in: D. Tilman

and J. Grace,

eds. Perspectives on plant competition. Academic Press).

In nutrient-rich habitats, herbaceous plants prevail on both sides, but the

vegetation is still very different (non-grazed = left; intensely grazed =

right) – where do rare species flourish?

We are studying

this right now, using various methods (line transects, transplantations,

seeding experiments, short-term manipulations of grazing intensity). The

results are still preliminary but an interesting paradox is emerging. Sheer

censuses indicate that the majority of the rarities are grazing-favored, whereas the results of transplantations and short-term

grazer exclusion experiments are ambiguous or indicate that the most rarities

are negatively influenced by grazing.

The likely

reason for the apparent paradox is different kinds of grazing impacts operate

in entirely different time scales; the negative impacts are direct and rapid,

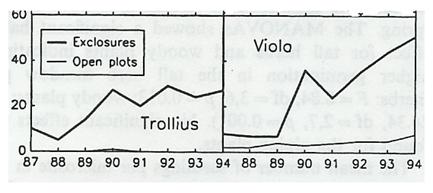

the positive impacts are indirect and slow. An example is provided by Viola biflora (not

a rare species, but one we have studied in different contexts). In our previous

experiment, which lasted for 10 years, we found that this species is strongly favored by exclusion of grazers (left panel, from Moen and Oksanen 1998, Oikos

82: 333-346). On Raisduottar, however, where the involuntary “fence

experiment” has lasted for 40 years, this species is among the ones that has

most pronounced gained from intense grazing; its yellow flowers decorate the

summer range (right panel, right side), while it is practically absent on the

other side of the fence (right panel, left side). This indeed depends on the

nutrient pool; if the bedrock is sufficiently nutrient rich, V. biflora

abounds on both sides of the fence, but its habitat amplitude is wider in areas

where reindeer keep nutrients in rapid circulation.

Even the tall herb meadows in the non-grazed areas

(previous page, left) are, in fact, products

of past grazing. In the absence of reindeer, such sites would be occupied

by willows, with the tall herbs just as a minor component of the community.

However, willows are grazing sensitive and disappear from areas preferred by

reindeer. Tall herbs are fairly grazing-sensitive, too, but survive at low

densities and quickly take over when grazing ceases. Once the tall herbs have

become dominants, they easily exclude willow seedlings as willow seeds are tiny

and provide no resources for the seedlings. During the 40 grazing-free years,

willows have thus got foothold only in disturbed sites (around power line

posts, along the access road, in eroding river banks and on gravel bars in

braided streams). In all other sites, the tall herbs have stood their ground,

indicating that history counts on the

tundra.

The

project is going on; please recall that the above results are preliminary.

Like all

arctic-alpine projects, the work on Raisduottar requires a team with a good working spirit, willing to live in a remote place

under primitive conditions (only Sámi tepees available as accommodation in this

area). I have indeed had the advantage of having such teams – below the 2004

work group collecting Saxifraga oppositifolia for

transplantation experiments.

…and indeed, the

team must thrive in the outback, as my students and collaborators have done –

coffee break on the tundra